A Rebuttal to the Arbitrary Arguments for “Real Art”

AI is a tool that people can use to express themselves and art is about expression. These are the simple truths at the heart of my “AI is Art” Campaign, which I felt compelled to make after reading some of the attacks on AI Art and AI Artists on anti-social media. I had a few key goals in mind as I made these pieces: 1) To show that new tools, art forms, and provocative, unconventional artists have been routinely attacked and dismissed in the past. 2) To promote a better understanding of what art is, or at least to make people question their assumptions about art. 3) To show how human development, in art and every field one might pursue, depends on others. “No man is an island,” as they say. 4) To express these ideas through AI Art creations.

The debate around AI and art centers on a few frequently repeated talking points. One of these is the misconception that the AI itself is the artist, because it is, “doing all the work” and/or, “making all the choices,” and since it is only a lifeless program it can’t bring any life to the work. This fundamentally misunderstands the nature of AI and the intentionality of those who create with it. Critics will say, basically, that it is “too easy” to create an image with AI. All you need to do is, “speak a few words,” and the AI fills in all the details. “Making a prompt is not making art.”

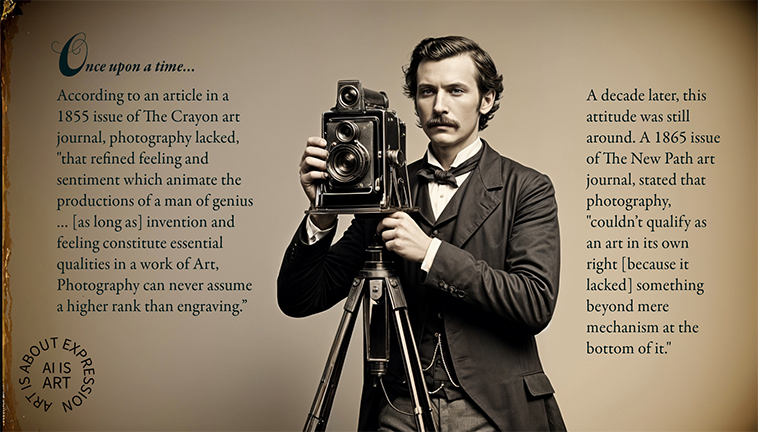

I have tried to explain that all you need to do with a camera is to push a button and the machine does all the work, but this only seems to make the critics more enraged. Typically, they lecture me, like I’m an idiot: “Photographers make a lot of choices about where to place the camera, how to frame the shot, what kind of camera to use, what time of day to shoot, etc. And they have spent years of study and practice to do these things correctly.” In reality, however, these are things that photographers might do. They are not universal or necessary practices to create art with a camera, or your smartphone.

Most people, or at least most of the people I have observed, can’t even figure out if they should hold their phones vertically or horizontally when taking a picture. They don’t understand what would be the benefit of one vs the other, and they certainly do not have years of study and practice behind them. Nevertheless, they can have intentionality. They can wish to express something, and they can take a photo that helps them express this. They can make art. They can be artists, even if much of their work isn’t all that aesthetically pleasing or complex.

The majority of AI, text to image critics, that I have talked to, read, or watched, seem to be unaware of how much time and effort can go into a piece of AI Art. Finding the right reference image or images. Drawing your own reference image(s) or making and manipulating reference images in Photoshop to better guide the AI to the exact vision in your head. Using and combining different styles, models, and settings with an AI program and using multiple AI programs to bring just the right combination of styles and looks together. Then further touching up or enhancing the images with Photoshop and/or other image enhancement programs. Several people I have met, who are now working with AI, have come to it with a wealth of knowledge and experience from other fields, like photography or painting. None of this is necessary to identify AI images as, “real art,” but critics pretend like it isn’t even a possibility, because they are actively seeking ways to dismiss AI rather than making any effort to understand it.

These same critics also tend to know little about the history of photography and how it was not considered art when it was first developed, because it was just a mechanical process, lacking in a soul. It is uncanny how much the critics of AI-based art sound like the critics of camera-based art. This is no random coincidence. It is a red flag, pointing to fearful and misguided thinking.

“But all you’re doing is just telling a program to do something and it does it,” the critics continue to insist. “You can’t be a real artist if you didn’t actually craft anything yourself. You can’t hire artists to make art and call yourself an artist just because you told them what to do.” Putting aside the fact that this is what I am doing with a camera, or a drum machine or Photoshop (how many people can keep a perfect beat or draw a perfect circle without such tools to assist them?) critics are also ignoring the difference between an artist and a craftsman.

Some artists are great craftsmen. They can paint or sculpt with such exquisite detail that you half expect their subjects might get up and walk away. But others are more compartmentalized. Why should someone who has a vision but lacks the craftsmanship to create it physically, be barred from recognition as an artist? And why should a great craftsman, who perfectly follows instructions down to the smallest technical detail, but makes no fundamental choices, be seen as anything other than a craftsman? This is not to belittle craftsmen or the beauty of the work they do, but only to say that there is a distinction to be made here. One field in which we commonly recognize this distinction and give it little thought is architecture.

Who created the Waterfall House? Frank Lloyd Wright. Who is credited as the artist behind the Vietnam Memorial Wall? Maya Lin. In both cases, and basically, all architectural examples you can name, skilled and unskilled laborers, along with machines, executed the vision of the architect, but the artistic credit remains with the architect alone. They were the ones with the vision, the intent, directing the building process to meet what they wished to express. Rarely do architects do any of the physical work necessary to bring an idea from their mind into the real world, but they are the creators of the work.

AI is an extremely sophisticated tool, compared to the artistic tools that came before it, but it is still, fundamentally, performs the same function as these other tools. It is executing the artist’s vision, just as craftsmen, unskilled laborers, and machines do in the execution of an architect’s vision. The AI performs functions it was programmed to do, without any intentionality or desire. It is a mathematical formula, capable of great craftsmanship, but that doesn’t stop the artist who uses this tool to express their ideas from being an artist.

Again, when I’ve said this to critics of AI, they lecture me like I’m an idiot. “Architects draw up plans, they don’t just speak words,” they insist. “And they have spent many years working and studying to know what is necessary to make a structure fundamentally sound, so it doesn’t leak, or collapse, or something bad.” This is all, presently, true, but irrelevant. There may come a day when architects need only speak their ideas and an AI will draw them out, and redraw them until they meet the architect’s vision. AI may also allow people with little or no knowledge of the limitations of steel in a given situation, or other technical details, to still create magnificent buildings, sculptures, and art installations, without years of study. Nevertheless, they will still be artists. What critics are doing, and it is a natural impulse in many people, is to stay, “Here is the line I am comfortable with. You must put in X amount of effort and/or have Y amount of education before I am comfortable calling you an artist.” These are arbitrary rationales for the irrational. This is a denial of what art is. Art is about expression.

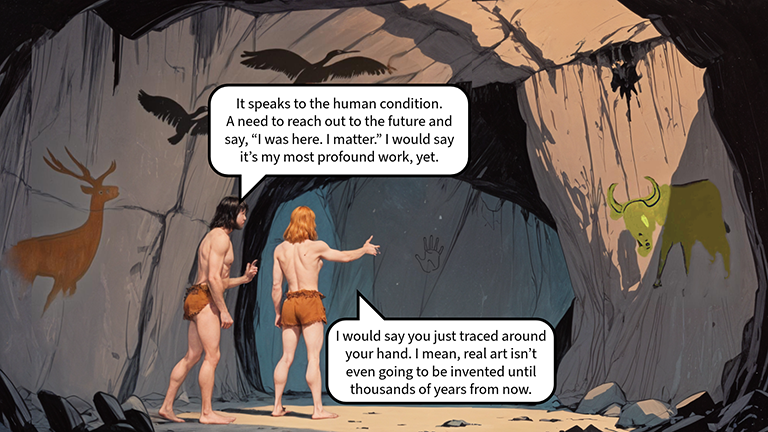

Another popular line of argument among AI critics is that AI is “stealing” or “plagiarizing” from “real artists” without giving them any credit or compensation. These accusations overlook a crucial point: Every artist, like every person, learns from past and present human beings. We are social creatures. This is not to say that we simply like to talk to and have contact with others. We are utterly dependent on others for our survival, and any achievements we actually make, “individually,” are simply taking a new step on a very, very, very, long road, that others traveled to get us here.

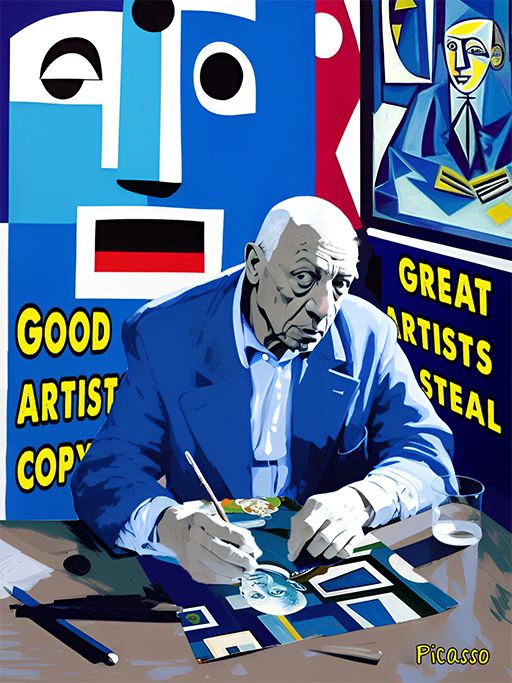

Artists build upon the work of those who came before them, and the works of their contemporaries, as people in every field do. No artist works in a vacuum. Every painter, photographer, musician, etc., learns far more from others than they could ever have created or discovered on their own, within the span of one, oh-so-short human lifetime. Picasso allegedly put this in a very provocative way –- “Good artists copy. Great artists steal.” –- which I used as the basis for one of my earliest AI pieces.

A more elegant way of putting it is that we are, “standing on the shoulders of giants,” which I used as the basis for one of the AI is Art pieces below. This isn’t some silly affirmation or slogan, nor is it a contingent possibility that occasionally applies to particular situations. This is the way human development, good and bad, develops. Did you invent the Internet, computers, audio recording, video, and film? Let’s take it back to more basic things than these, did you invent the wheel, story structure, the English language, or math? We take 99.99973% of what we have and what “I can do” for granted. We don’t want to acknowledge that each of us has actually done very little, in the grand scheme of things. We want to believe that because we worked hard, and sometimes sacrificed much, our achievements are mostly our own. But, in a very fundamental way, this isn’t true and never can be.

Imagine that Einstein had been born 20,000 years ago. Certainly men and women as intelligent as our shorthand symbol for genius did live at that time, and all times in between. But their ability to accomplish anything would be dependent on where and when they lived. Einstein, 20,000 years ago, would not realize that E=MC2. He wouldn’t know that light moves in waves or that everything is made up of atoms. He wouldn’t even understand that such a concept as “physics” existed. He may do great things, compared to others around him. He may find a faster way to start a fire or a means by which a spear can be thrown further and harder, but that’s about it. Even if Einstein had been a contemporary to Newton, he would not have had the basis to question Newton’s ideas and discoveries. He needed the giants that came before him to have any chance of seeing a bit further, by standing on the high ground that countless generations made possible.

When AI “learns” (i.e. incorporates new data) from the vast array of artworks time and human effort have made possible, it is essentially doing what every artist does. What writer living today asked permission to learn from Shakespeare or Kurt Vonnegut? What painter today compensated Rembrandt or Picasso? But they will say that this is okay because they had to study and work diligently to synthesize influences into their own style. They feel offended at the scale and speed of AI’s learning process and how it allows others to “cheat” their way into making art. They are so offended that they cannot even bring themselves to call it “art;” in many cases. This is an understandable feeling, but not a logical argument.

Technology often reduces the time needed for tasks and makes leaps possible that simply could not happen without technology. It also changes what we need to know, to survive and thrive. How many people today can even build a fire? For most of the time that human beings have been on this planet, knowing how to make a fire was essential in so many ways and they would think us stupid or pathetic not to know this. To bring it to more recent times, movies were originally shot on film, which cost a good deal of money for the camera, film stock, lights, etc. Then, after you shot the film you had to pay more money to process it in a lab and hope it turned out. Then you had to physically cut the negative into pieces and tape those pieces back together, repeatedly to make a “final cut” of the film. This greatly limited the amount of footage you could cut together in your lifetime and required training and effort, along with money, far greater than anything needed by a teenager with an iPhone today. But that teenager has to potential to shoot and edit far more footage, and perhaps emerge as one of the greatest storytellers of all time. Do we dismiss this as not being, “real art,” because they didn’t need to work as hard for it? If that is your criteria for measuring “real art,” then many, if not most artists, are becoming less and less of an artist with each passing generation.

However, if we measure who is an artist by their ability to bring a vision into the world, then all the rest doesn’t matter. Your tool or medium. Your education or lack thereof. Your level of effort or need to sacrifice. These things are not the issue. Did you have intentionality? Did you have something to express? Did you find a way to express it? These are the things that matter. And using AI, like any other tool, doesn’t make you a “thief,” “plagiarizer,” or unAmerican. You used a tool to do something that once took greater effort. That’s all.

The history of the post-Renaissance world has largely been a history of democratization. What only the wealthy, the gifted, the physically strong, the select few could do, more and more people are now able to do. AI may be a great leap in this continuum, but it does not lay outside the continuum. all arguments against the use of AI art, or calling it “art” and its practitioners “artists,” are, at heart, emotional reactions that are akin to all the reactions against democratizing tech and forces that came before it. “Those people,” didn’t work for it. “Those people,” didn’t follow the same path or abide by the same limitations that we did. “Those people,” don’t deserve this. If these arguments were correct, then none of us deserve the vast majority of what we have.

The “AI is Art” campaign.

I hope these pieces will shake a few people out of their complacency and give them a fresh perspective. Maybe then, we can begin to discuss the subject constructively rather than simply reacting to it.

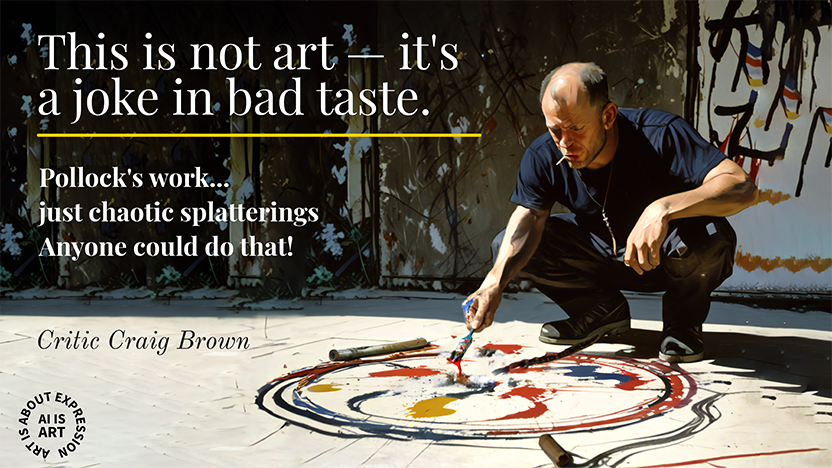

Jackson Pollock. This was the first thing that came to mind when I conceived the AI is Art campaign. Jackson Pollock was, and still is, dismissed as not doing “real art” because there is an element of chance and randomness to his work. He has intentionality, in the colors and general movements, but he is not painting any particular real world objects, even in an abstract way. It is a complete abstraction. And his critics reflexively said, “Anyone could do that!” which is now what is said about the use of AI.

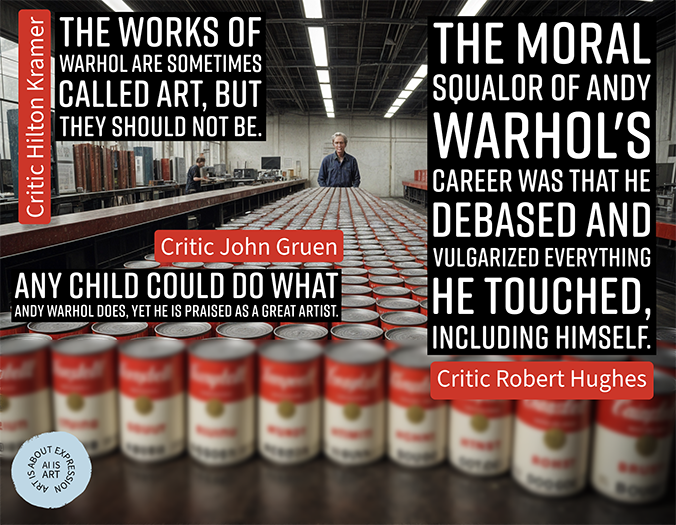

Andy Warhol. Warhol’s adaptation of everyday things, like soup cans, and his use of photographs taken by others, etc., was denounced as not being “real art” and accused of being “theft.” They were also dismissed as something, “a child could do.” It’s a standard refrain.

Photography. Photography marks the first time that a mechanical device was doing much of the crafting of a work of art. The reaction against this “soulless” device, which somehow stopped the artist behind it from being an artist, is the closest thing you will find to a one-to-one relationship between past criticism of unreal art and today’s criticism of AI-based art that isn’t art, or so they say.

Impressionism / Claude Monet. I know Monet was dismissed and looked down upon in his time, but it wasn’t until I decided to incorporate him into the AI is Art campaign that I found out that the father of Impressionism didn’t call his style, “Impressionism.” He named one of his paintings, “Impression, Sunrise” (1872), which I put at the center of this ad, and that was the jumping off point for critic Louis Leroy to belittle the movement as mere impressions; too incomplete to be “real art.”

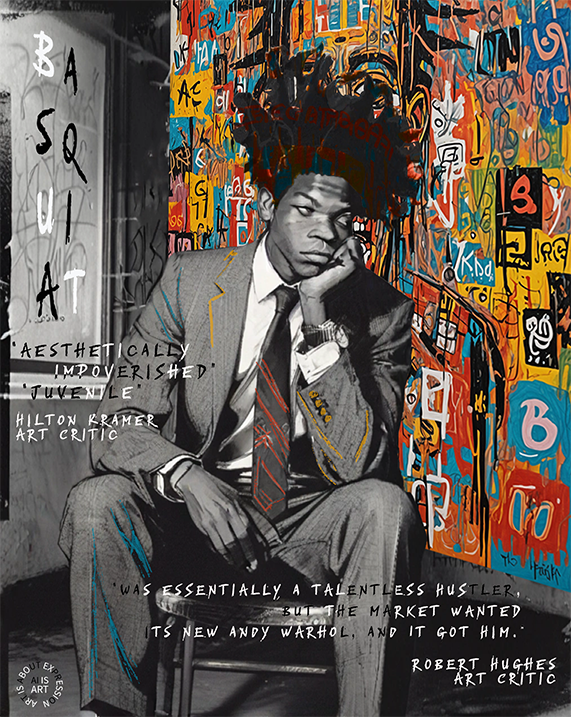

Jean-Michel Basquiat. One of my favorite examples of a non-artist, artist, who did “juvenile” work that anyone could allegedly do. Of course, as the first superstar African American artist, attacks on Basquiat were further fueled by racism.

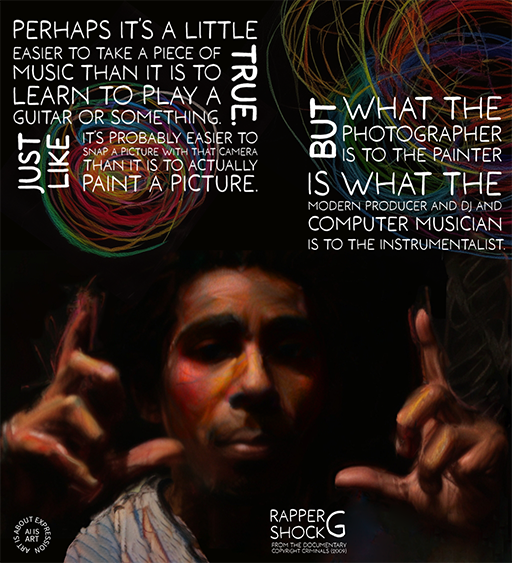

Sampling / Shock G. This one comes from a great documentary about sampling and rap music, Copyright Criminals (2009), which also relates to visual art and the complaints about AI.

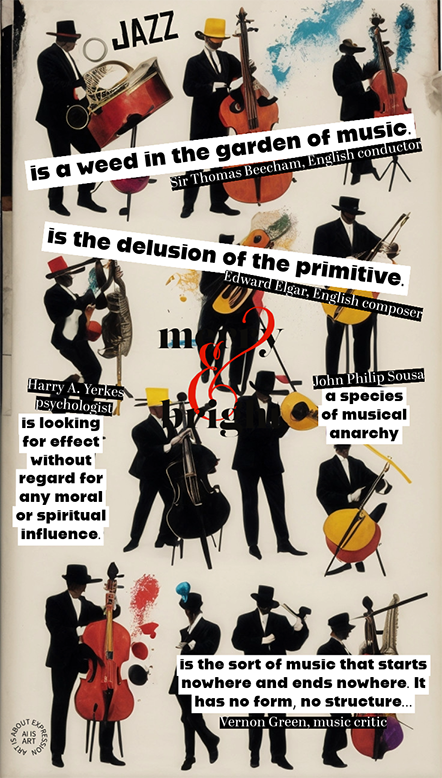

Jazz. Jazz music has become a point of pride for Americans. A form of music that broke with the constraints of European conventions and proved that the United States could do innovative and amazing art. But that is not the way it was seen at its inception, or for many years after that.

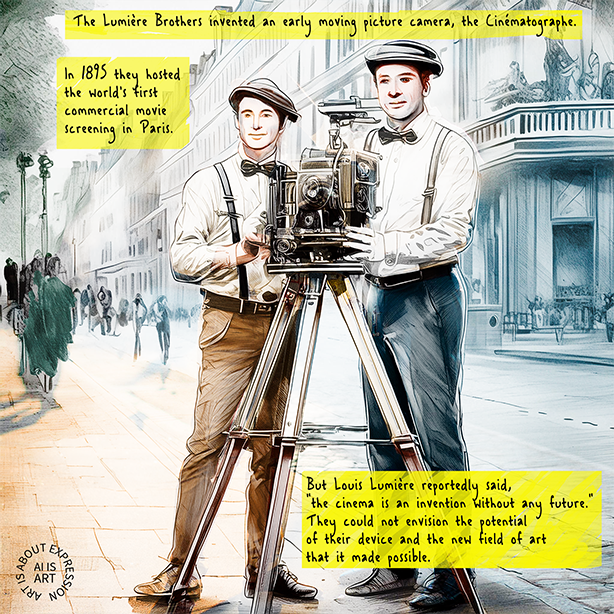

Cinema / Lumière Brothers. Film, the movies, were a radical re-imagining of how to tell a story, that enabled a new breed of artists to bring their dreams to life, more viscerally than anything done before. The twentieth century can be examined and defined in many different ways, but it was unarguably the Century of Cinema. And yet, the two brothers who likely did more to make this possible than any of their contemporaries, did not seem to understand the potential of what they created. In their defense, seeing into the future is no easy feat. Today’s critics of AI Art have no idea of the wonders that may be created with it, that cannot be possible without it, yet they act as if they are all-knowing oracles who have seen the downfall of art, which AI will allegedly bring, and they have preemptively judged AI guilty for it.

Text to Image Art. This one depicts me, or anyone else using AI to create art on their computer. The image this imaginary artist is working on features two, more traditional artists, a photographer and a painter, capturing the beauty of a waterfall, as they see it. I like the Warhol quote, but the Hubbard one, “Art is not a thing, it is a way,” is my favorite. It is the essence of what AI Art Critics do not, or cannot bring themselves to understand.

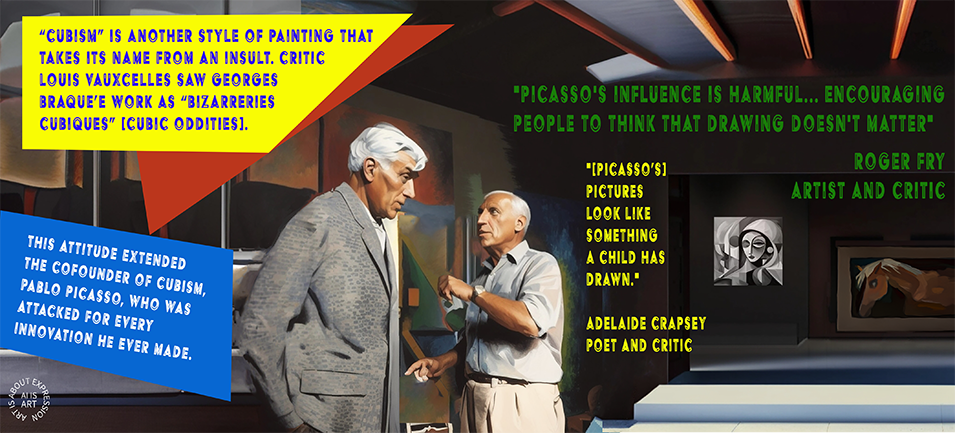

Cubism / Pablo Picasso. Like Impressionism, I was surprised to find that Cubism was another insult. It was originally applied to the work of Georges Braque, but Picasso is the Cubist Artist everyone still remembers. Picasso has become a shorthand flashpoint for everyone and everything that makes people question what art is, or isn’t. I can’t help but think, “What would he have done with access to AI?” I am certain that he would not reject it and say it wasn’t “real art.”

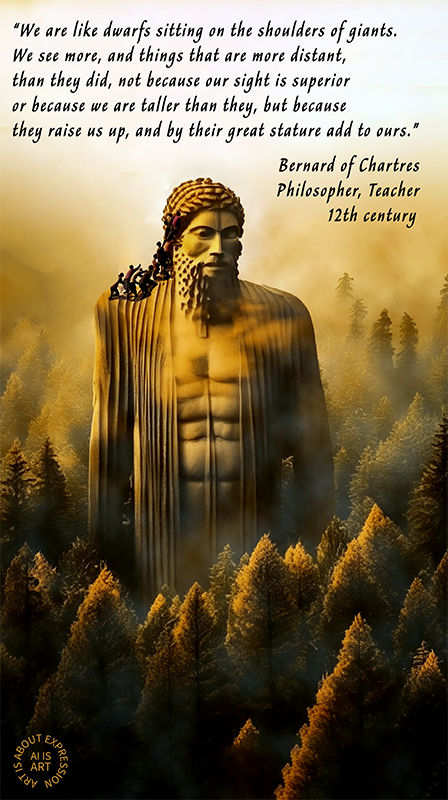

Standing on the shoulders of giants. I end this series with the wise words of Bernard of Chartres:

“We are like dwarfs sitting on the shoulders of giants. We see more, and things that are more distant, than they did, not because our sight is superior or because we are taller than they, but because they raise us up, and by their great stature add to ours”

This is the human condition. We should recognize it and be far more humble because of it. At the very least, we should not dismiss or attack artists as non-artists, just because they happened to be born on a higher shoulder than those who came before them.

It should be noted that I tried making this one with actual giants, i.e. things that looked like living creatures, but it didn’t work. The statue better represents the fixed nature of what came before, while also suggesting that it could crumble to pieces, forcing humanity to start over again.

P.S. Speaking of statues, have you visited the Thinker Gallery?

Leave a Reply