A Look at “The Influence of Soros”

George Soros, the name evokes diverse reactions. To some, he’s a financial titan, a “philanthropic statesman” advocating for open societies. To others, he’s a shadowy manipulator, fueling conspiracies and manipulating world events. Emily Tamkin’s “The Influence of Soros” delves beyond the caricature, offering a nuanced portrait of the man and the enigma he embodies.

Born György Schwartz in 1930s Hungary, Soros’s life began under the dark cloud of Nazi occupation. As Tamkin details, “he survived by living under a false identity, his father Tivadar using his wit and connections to help others do the same.” This experience of precarity, of witnessing injustice firsthand, would profoundly shape Soros’s worldview.

Soros’s financial acumen is undeniable. His legendary 1992 bet against the British pound solidified his reputation as a bold risk-taker and earned him the dubious moniker “the man who broke the Bank of England.” Many investors realized that the pound was overvalued, but that doesn’t mean that any of them were the cause of England’s problems at the time. And the fact that Soro’s bet was large enough to be widely noticed doesn’t change this.

Tamkin emphasizes, “finance was never an end in itself, but a means to an end: the pursuit of an open society.” This pursuit manifests in Soros’s extensive philanthropic endeavors. The Open Society Foundations, his brainchild, have channeled billions towards causes like democracy, human rights, and education worldwide. “Soros believes,” as Tamkin puts it, “that a society thrives when its citizens are empowered to think critically, engage freely, and hold their leaders accountable.”

However, Soros’s activism has also made him a lightning rod for criticism and conspiracy theories. His support for progressive causes and figures has fueled accusations of globalist agendas and undue influence. Tamkin delves into the anatomy of these narratives, revealing their often antisemitic undertones and their exploitation of anxieties about globalization and social change.

One particularly absurd, but popular example Tamkin cites is the claim that Soros funded the migrant caravans arriving at the US-Mexico border, a demonstrably false narrative used to demonize both Soros and the migrants themselves. As Tamkin argues, “these conspiracies reveal a deeper fear of Soros’s ideals: a world where power is less concentrated, where voices are diverse, and where the status quo is challenged.”

The Long Shadow of Antisemitism:

It’s crucial to recognize that while several factors contribute to distrust and dislike of Soros, antisemitism arguably fuels the most insidious and persistent narratives. Soros, unfortunately, has become the modern-day embodiment of the “Rothschild” archetype, the shadowy Jewish financier manipulating markets and societies for personal gain.

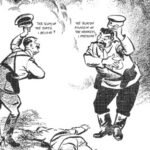

Just as Soros was labeled “the man who broke the Bank of England,” Nathan Rothschild was once accused of buying up all of England by manipulating the market after the Battle of Waterloo. This fabrication, despite having no basis in reality, became ingrained in popular consciousness and was repeated for generations; culminating with the Nazi propaganda film like “Die Rothschilds” (1940).

Soros’s philanthropy is often painted as a smokescreen for nefarious goals, echoing the age-old trope of the Jewish philanthropist with hidden agendas. The very act of supporting progressive causes becomes suspect, fueled by antisemitic stereotypes about Jewish control and subversion.

The Philosopher Behind the Philanthropist:

Another crucial aspect of Soros’s worldview, often overlooked, is the profound influence of philosopher Karl Popper. Popper’s book, “The Open Society and Its Enemies,” became a touchstone for Soros, shaping his understanding of freedom, democracy, and the dangers of closed societies.

Popper argued for a society open to critical thought, individual liberty, and the free exchange of ideas. He saw closed societies, driven by ideology and dogma, as breeding grounds for intolerance and oppression. This philosophy deeply resonated with Soros, who saw his own experiences under Nazi occupation as a chilling example of a closed society’s dangers.

Soros’s commitment to open societies, manifested in his philanthropy and activism, can be directly traced back to Popper’s ideas. Understanding this intellectual lineage adds another layer of complexity to his story and helps dispel simplistic narratives about his motivations. Somewhat ironically, or perhaps tragically, it is worth noting that Popper also identified extremists, both the Communist left and the Fascist right, as holding a conspiracy theorist mindset, where reality could be whatever they needed it to be.

Beyond the Caricature:

Ultimately, “The Influence of Soros” is a captivating exploration of a complex figure. It goes beyond hagiography or demonization, instead offering a balanced look at Soros’s life, legacy, and the controversies surrounding him. Tamkin concludes by asking, “Can a single individual, no matter how wealthy or influential, truly alter the course of history?” The answer, as the book demonstrates, is far more nuanced than any simple narrative.

Leave a Reply