Echoes from the Second World War

It was the second-to-last episode of The Handmaid’s Tale that got me thinking about all this. June (Elisabeth Moss), bruised but unbroken, shouts to the crowd before she is about to be hanged from a crane:

“Don’t let the bastards grind you down!”

A line of defiance. A curse hurled upward. A call to action. A phrase that feels like it was born in the streets with a Molotov cocktail in hand. Something shouted by punks, or scrawled on the inside cover of an anti-establishment manifesto. It feels like it belongs to the Weather Underground, or the British squatters scene of the 1970s. Maybe a greeting coined by Sid Vicious to close out Sex Pistols shows.

But it’s not. Or rather, it didn’t start there.

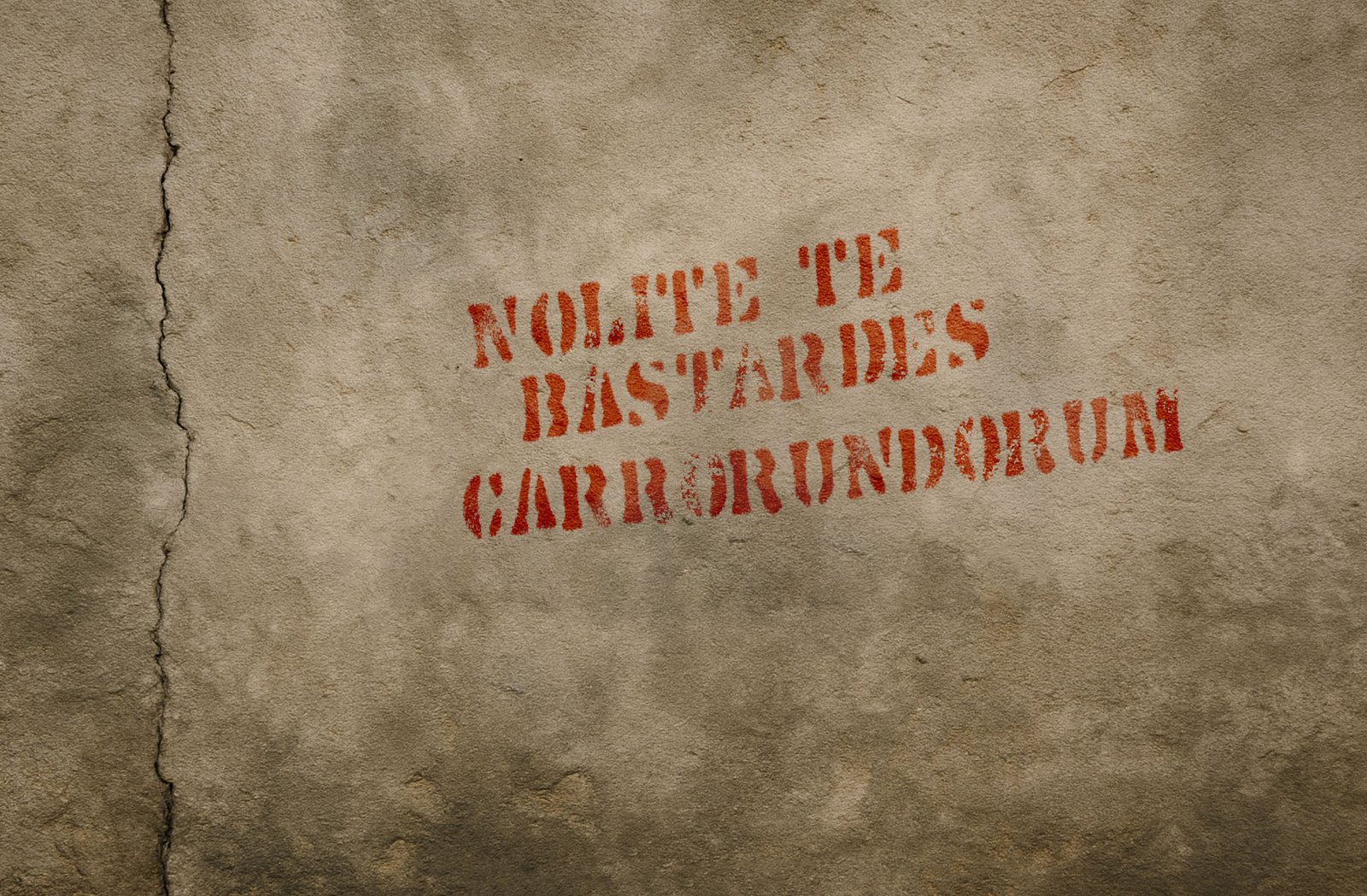

The line shows up in Margaret Atwood’s original 1985 novel The Handmaid’s Tale, and the first season of the show, carved into a closet wall by a former Handmaid who didn’t make it out. Offred (June’s slave name) finds it—nolite te bastardes carborundorum—and doesn’t know what it means. Later, the Commander smugly explains it was a joke from his schoolboy Latin class.

Which it was, or rather, it was a joke from Margaret Atwood’s schoolgirl Latin class. But it didn’t start there either.

Bastardized Latin and Cultural Repurposing

The phrase “Illegitimi non carborundum”—a different version of mock-Latin for, “Don’t let the bastards grind you down”—was a running joke among British and American troops during World War II, who used it interchangeably for the enemy and their own bureaucracy. It’s not real Latin, just Latin gibberish slapped together to sound official and defiant at the same time. It’s funny how the language of Ancient Rome still makes things feel official, dignified, important, even when it’s part of a joke.

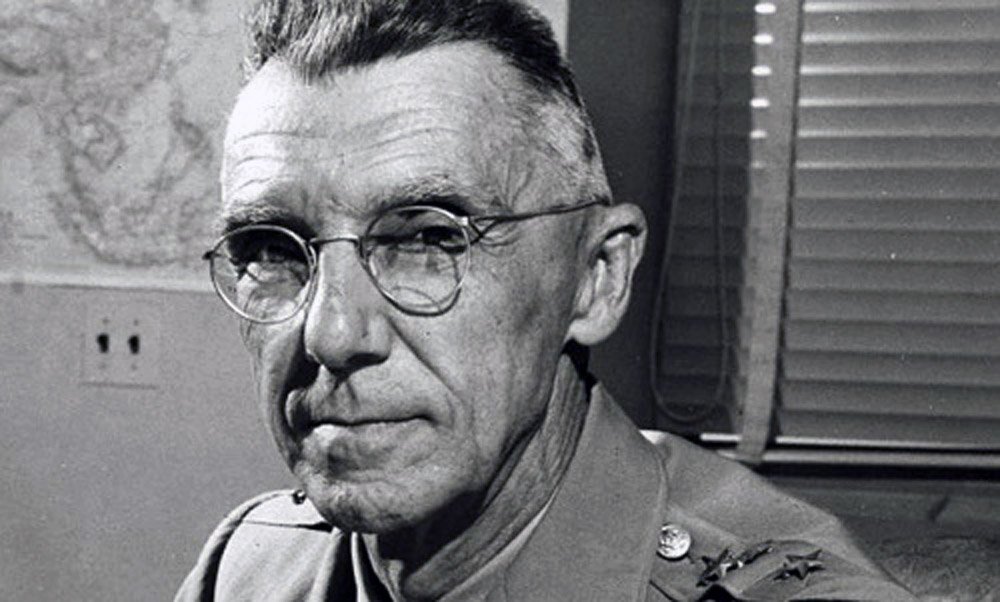

It was the legendary General “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell who became most closely associated with the term. As commander of U.S. forces in the China-Burma-India theater—one of the least glamorous and most politically maddening parts of the war—he made the phrase his personal motto and had it framed on his desk. It went well with his cranky, sharp-tongued leadership style. “Don’t let the bastards grind you down” wasn’t just a joke, it was his operating philosophy, and perhaps his means of maintaining his sanity.

I find it endlessly fascinating to pull back the layers on things like this—words, ideas, products—anything that might be reappropriated or adapted, over time. How does meaning evolve, and what can we discern about the past and the present from the way things have changed? Every artifact and memory is a new window on the past, a new way to make connections, and find new understanding. With that in mind, here are some more things you may not associate with the Second World War, or may not realize how they have been modified, reshaped, and transformed.

Not Just a SNAFU

Some of the slang we take for granted now came from those same soldiers, many of them conscripted, many of them angry, scared, and trying to joke their way through Hell.

You’ve probably heard someone call a mild mishap “a snafu.”

But originally, SNAFU stood for:

Situation Normal: All Fucked Up.

Much like with FUBAR:

Fucked Up Beyond All Recognition.

Today, “snafu” sounds like a scheduling error. Back then, it was gallows humor for a supply line that never showed up or a commanding officer who got your platoon killed.

It’s worth remembering, because people often look back at the 1940s and imagine it to be a more polite, formal, sedate time; like the post-war Father Knows Best, Leave It To Beaver TV shows of the 1950s made America out to be. But that wasn’t the real soundtrack to the Second World War. These men, and a good many women, swore. They mocked everything. They made up words to take the edge off. They were inclined to live life like there was no tomorrow, because there might not be.

And some of their words, like “snafu,” still bounce around today. Just drained of their original bite.

That Jeep You Drive

Then there’s the Jeep.

Still sold today, still marketed as rugged, off-road, American-made freedom in vehicle form. But the name wasn’t dreamed up in a Detroit boardroom. It came from army slang. The official designation was “G.P.” for “General Purpose.” Say it fast a few times and you get it: Jeep.

Soldiers turned the abbreviation into something easier to say, and more fun to yell across a muddy motor pool. The nickname stuck. The brand came later. Now you can buy one with leather trim and heated seats. But it started as a rattling little workhorse hastily bolted together for war.

Is That Rosie the Riveter?

Another thing that’s been drained of its original bite:

Rosie the Riveter.

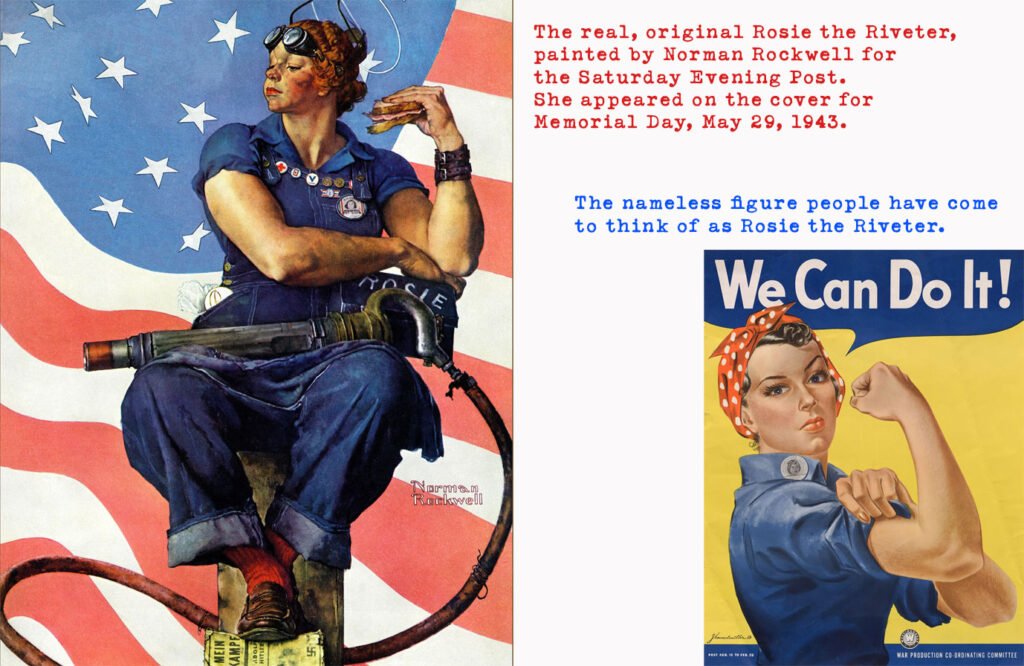

You know the image. Red bandana, rolled-up sleeve, blue jumpsuit, flexing hard with the slogan: We Can Do It!

But here’s the twist:

That woman? She’s not Rosie.

She wasn’t named Rosie. She wasn’t even famous.

The “We Can Do It!” poster was an internal Westinghouse morale piece, made as part of the government’s War Production Coordinating Committee, to boost wartime factory morale and it was displayed to workers for only a couple of weeks in 1943.

The real “Rosie the Riveter”—at least the one people were referring to at the time—was a Norman Rockwell painting published on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post. She’s beefier, less glamorous, with red hair, has paint on her face, and is literally stomping on Hitler’s Mein Kampf. But that image was copyrighted.

So when the feminist movement came looking for an icon in the 1980s, they picked the one they could use. The anonymous Westinghouse woman. Free to reprint, easy to stylize. And so the mix-up began. Now she’s Rosie, the icon, despite the facts.

SPAM, SPAM, SPAM, SPAM, SPAM, SPAM, SPAM, SPAM

Then there’s SPAM.

Yes, the meat.

Yes, the email.

Yes, the video game term.

It all comes from the same place.

During WWII, Hormel’s canned mystery meat became the go-to protein for U.S. soldiers. It didn’t spoil, didn’t require refrigeration, and could be shipped in absurd quantities. And it was; sixteen million cans per week at one point. Troops got so sick of it they started mocking it in song, in letters home, in graffiti.

But here’s the thing: they kept eating it. It kept showing up. And it kept shipping out—not just to soldiers, but to civilians in war-torn areas, especially in the Pacific.

In places like Hawaii, Guam, and the Philippines, SPAM became a staple. It was survival food. And after the war, it stayed. SPAM musubi, SPAM fried rice, SPAM with eggs. These aren’t wartime relics. In the Pacific, they’re cuisine.

Which brings us to a stranger, sad, and surreal aspect of the SPAM story: cargo cults. They sprang up on some Pacific islands during and after the war. When Allied forces landed with cargo planes full of food, supplies, medicine, and yes, SPAM, locals sometimes began to view these goods as divine gifts from the gods. When the soldiers left, some islanders built mock runways or carved wooden planes, hoping to summon the cargo back.

SPAM was part of that myth.

Spam wasn’t just food. It was proof that magic had once visited them.

And then there’s the digital afterlife. Thanks to Monty Python, “SPAM” became the go-to term for repetitive, unwanted content. From there, it entered email. Then gaming. Now, my kids say “I’m spamming the button!” when they’re hammering a controller trying to survive.

Cheap wartime meat → Pacific staple → British comedy sketch → junk email → Fortnite slang.

That’s one hell of a supply chain.

Boobs and Booby Traps

Let’s switch back to something a little darker: booby traps.

Today it sounds like a joke term. Maybe something out of Home Alone, or a cartoon jungle sequence. But in WWII, booby traps were real, deadly, and often invisible until too late. And the name?

“Booby” originally meant a fool or simpleton. A booby trap was something meant to catch the unsuspecting.

But by the time U.S. troops were getting stationed abroad, the term had picked up a very different implication.

The military started issuing warnings in the form of propaganda cartoons—many starring Private Snafu, an animated soldier who always did the wrong thing. One of the themes? Women as literal booby traps. Seductresses with grenades in their bras. Beautiful spies spreading disease. The cartoon logic was clear: look out for curves and tripwires.

It’s sexist and over-the-top, but also a weird snapshot of how deeply the war merged fear, sex, and language. Even the word “booby” got weaponized.

What’s Past Is Prologue

World War II wasn’t just a military conflict; it was a linguistic event, a design event, a cultural event on so many levels. It reshaped how people talked, dressed, ate, cursed, thought, and joked. It gave us not just Jeeps and SPAM, but ways of thinking that keep surfacing in the corners of our lives.

Some of the connections are obvious. Others are buried. But they’re there, in our slang, our memes, our slogans, our icons.

History doesn’t sit still. The past gets quoted, misquoted, copied, and commercialized. Rosie loses her name and becomes a sticker on a laptop. SPAM becomes something you delete, then something you do. SNAFU becomes a clerical error.

But if you pull back the layers, you can still find the original pulse.

They weren’t trying to make history. They were trying to survive, and stop the fascist threat that had consumed the world.

And that sentiment has not changed. You can hear it in a voice yelling from the gallows:

Don’t let the bastards grind you down.

Leave a Reply