Lessons from History on Democracy’s Fragile Dance with Creeping Tyranny

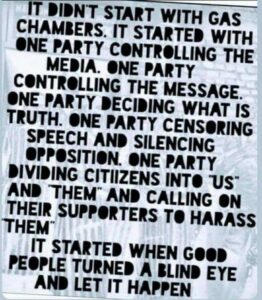

Benjamin Carter Hett’s “The Death of Democracy” is a poignant exploration of how the German Republic fell into Hitler’s hands. It is also a warning about the current state of the American Republic. Hett quotes journalist Dorothy Thompson — the first American journalist to be thrown out of Nazi Germany in 1934 — who astutely observed, “We cannot defend democracy by denying facts.” It is a chilling reminder that “fake news” and disinformation campaigns are nothing new. The erosion of trust in factual information created fertile ground for manipulation and the rise of extremist ideologies in Weimar Germany, much the same way it is doing in the United States today.

In the aftermath of “The Great War” (World War I) the last German Kaiser abdicated and a new, democratic nation emerged from the ruins. Known as the Weimar Republic, after the city where its constitution was adopted, this new Germany was filled with promise and hope, despite the burden of the mess it was tasked with cleaning up and the often violent clashes between groups on the extreme left and groups on the extreme right. Berlin in particular looked like a model of modernity, with a flourishing arts scene and a widespread recognition of gay rights. Beneath this veneer of progress, however, the lingering wounds of war and the ongoing reality of economic instability fueled a pervasive narrative of national betrayal that overshadowed any reasonable understanding of history.

Throughout the war, even as the situation became dire and desperate at the front, the German public was given nothing but good news about how well things were going. When the military leadership finally admitted that they did not have the ability to carry on and everything would soon fall apart, they handed the situation off to the politicians, who created the new republic and surrendered to the nations allied against them. The Fatherland had not been invaded at this point and German troops still held foreign soil. “Why,” the average German was left to wonder, “had we given up?”

The Treaty of Versailles was formalized in June of 1918, six months after the fighting had stopped and long after German forces had been demobilized, leaving the Germans with no choice but to accept the harsh terms they were given. This was widely viewed as a national humiliation and completely unfair; ignoring the fact that Germany had imposed a similarly punitive peace on the new Communist government of Russia, with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, when the Russians gave up. The confused and selective understanding of the past that many Germans held was made much worse when Generals Erich Ludendorff and Paul von Hindenburg, the two most important wartime military leaders, began pushing the “Stab-in-the-Back” myth. Germany’s defeat was not the result of any military failings, but the treachery of politicians. The men Hindenburg and Ludendorff had once asked to salvage their failure where now presented as the cause of that failure. And, behind it all lurked the age-old lie that, “international Jewry,” was somehow behind everything. This insidious thinking spread into a widely accepted belief system, corroding faith in the republic and making extremist propaganda sound less and less extreme.

By 1923, hyperinflation had ravaged the German economy, decimating the middle class and greatly straining their confidence in the government. There had been a couple failed attempts on the part of Communists and Anarchists to seize power and start a wider revolution, but now came the time for violent rightwing extremists to stage their own major failure. Adolf Hitler, a previously unknown and unremarkable figure, had found a talent for leadership after the war and crafted an image of himself as a redeemer of German pride. One night he fired a gun into the air in a beer hall and declared that the revolution had begun. His, National Socialist German Workers Party, derisively called Nazis for short, was going to overthrow the government and create a new, truly German state, under the leadership of former General Ludendorff. Hitler did not yet have the confidence necessary to put himself forth as a supreme leader. The Beer Hall Putsch, as it came to be known, failed the next day, when government forces opened fire on Hitler and his followers in the streets of Munich.

In many ways, there is a vast gulf between the story of Weimar in the 1920s and recent American History, a century later. The United States has a well-established republic and nowhere near the kinds of problems that post-WW I Germany faced. But there are frightening similarities that we casually dismiss at our own peril. The worldview of Donald Trump and his MAGA supporters, who believe the 2020 election was stolen and a vast collection of other lies has a disturbing relationship to the Germans who demanded to know, “Who betrayed us?” And the devotion of both groups to some vague conception of patriotism or nationalism, with little or no understanding of their national constitutions or respect of the idea of a republic is disheartening. Then there is the failed, almost comically absurd January 6th attack on the Capital. What hubris to believe their victory would come so easily. It is so reminiscent of the Beer Hall Putsch that it hurts. Clearly there are lessons to be learned from Weimar, if you are willing to open your eyes and look.

After a brief stay in prison for his attempted treason, Hitler was released in 1925 and remained on the political fringe for a time, using this period to reorganize his party and hone his propaganda efforts; biding his time for a more opportune moment. The onset of the Great Depression helped bring electoral success to the Nazis, but this alone could not assure their ultimate triumph. As Hett’s detailed account of Weimar’s erosion makes clear, the agents of destruction advanced on many fronts, each with their own motives. There were personality clashes and power struggles within groups, as well as larger battles between groups. All of which came at the expense of the republic.

The Conservatives, Aristocratic and typically Monarchist Class, including the now President of Germany, Paul von Hindenburg, shoulder a great deal of the blame for the republic’s demise. They did not want to share power and tried to govern through emergency decrees, rather than consensus building. When this strategy proved to be untenable, Hindenburg finally agreed to make Hitler Chancellor, wishfully believing that the Nazis could be controlled. It should be noted, however — and Hett gives a rich retelling of this story — that a small group of Conservative Intellectuals and sincere Christians did work hard behind the scenes to appose Hitler and stop this madness in its infancy. Their leader, Edgar Jung, was arrested and murdered, along with hundreds of people from various political groups, in Hitler’s first act of mass murder, The Night of the Long Knives. Is it unreasonable to think that people like Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger could suffer a similar fate if the MAGA Militia types were given any actual power by a reelected and vengeful President Trump? I think not.

Another element of this story that is often ignored, particularly when told by those on the left, is the role the German Communists played in fragmenting and weakening Weimar. Had the German Communists united with the German Socialists, they would have represented a sizable opposition to Nazism. But the German Communists acted on orders from Stalin, and he wanted more chaos and no compromises. The Communists even voted repeatedly with the Nazis to dissolve government collisions and force new elections, in a further effort to destabilize the government. In the end, the German Socialist were the only ones who held any commitment to the preservation of the republic, and they could hardly make it work on their own.

Hett’s work goes a little further in time than this, with some valuable insights on the Reichstag Fire and Hitler’s final destruction of the Weimar Constitution, which was simply “suspended” for the dozen years of his dictatorship, but you can, and really should, read Hett’s book for yourself.

The Weimar Republic’s downfall serves as a cautionary tale about the perils of misinformation, political opportunism, and the gradual erosion of democratic norms. As we confront our own complex era, it is imperative to heed these lessons and vigorously defend the principle that any true republic is founded upon: A nation of laws and not of men. Following proscribed processes and cutting deals that never satisfy everyone may seem like an inefficient way to govern ourselves, but the alternative — handing everything over to a “strong man” who will “get things done” — is not the answer. Call it Fascism or Communism; call it MAGA or anything else you like. The end result will be fundamentally the same, a system that is only efficient at repression and death.

Leave a Reply