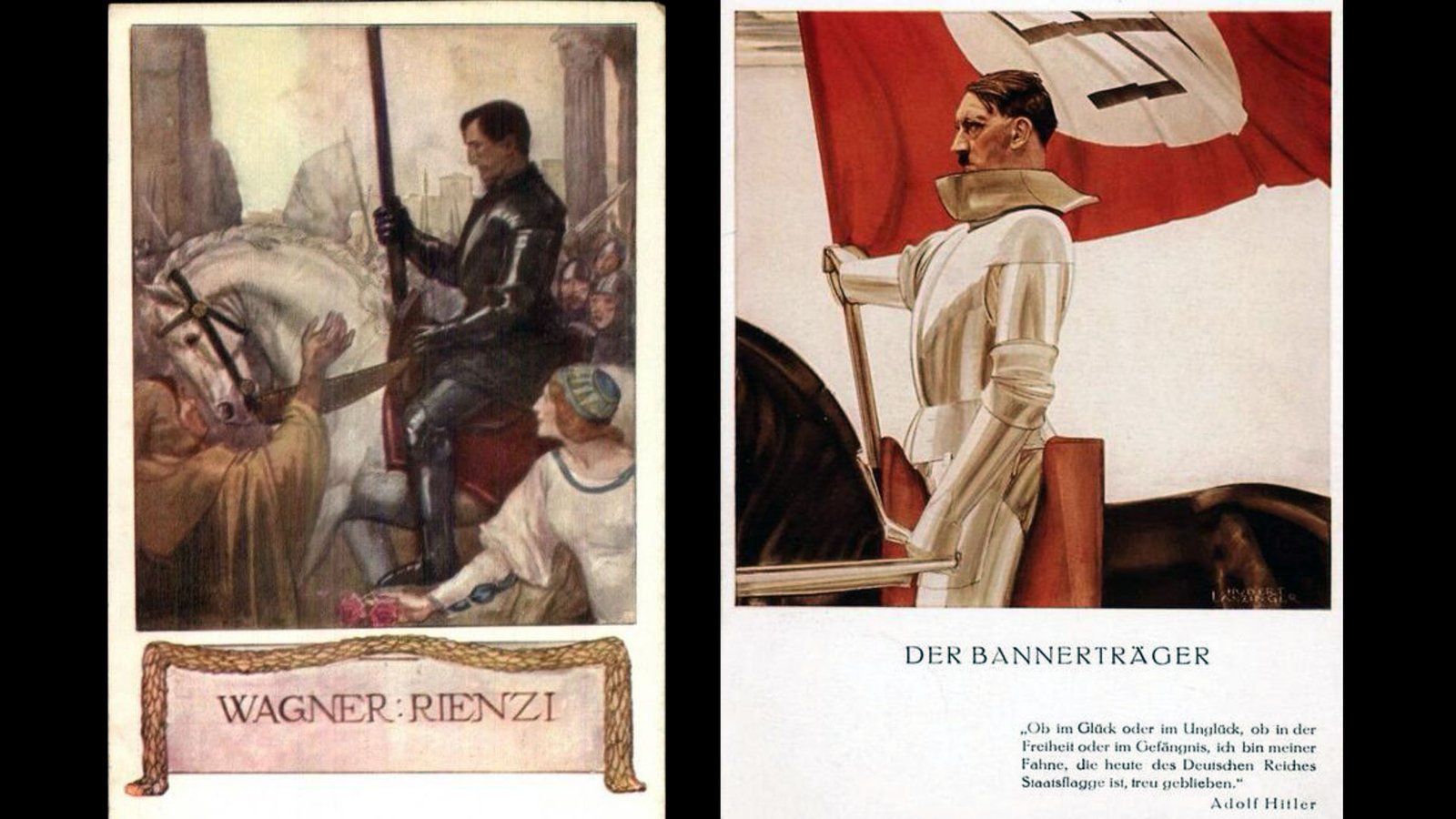

As a young man, Adolf Hitler attended a performance of Richard Wagner’s opera Rienzi with his friend August Kubizek, who later recalled how enraptured Hitler had been by the performance. After a long silence, Hitler led them to the Freinberg hill, clasped his hands, and “In grand, captivating images, he told me about his future and the future of his people,” Kubizek wrote. “He spoke of a special mission that would one day be his. I… could hardly follow him. It took me many years to understand what these hours of otherworldly rapture had meant to my friend.” Decades later, while attending the Wagner Festival in Bayreuth in August 1939, Hitler told a similar version of the story and declared, “That was the hour everything started.”

In Rienzi, the title character is a populist leader who rises through soaring rhetoric to lead the people of Rome, only to be betrayed and destroyed by those he hoped to uplift. For Hitler, the opera was not a cautionary tale—it was prophecy. He saw himself in Rienzi: the chosen leader, the voice of the Volk, destined for a grand, tragic finale.

April 27, 1945, was that finale in twisted form. In the depths of the Führerbunker, the rituals of death replaced the routines of leadership. Hitler was no longer issuing orders with the intent to win a war. He was staging the last act of a performance he believed would echo through history.

He met in private with Joseph Goebbels and Martin Bormann to revise his political testament—his final script. He spoke in fragments. His body trembled. His appetite was gone. He moved like a ghost. But even in this deteriorated state, he was still obsessed with how the world would remember him. Legacy was all that remained.

Around him, the atmosphere was heavy with dread. Communication lines were severed. The city above was burning. The Red Army’s artillery never stopped. Inside the bunker, the lighting flickered. Air was stale. Food supplies dwindled. It was not a headquarters. It was a tomb.

And yet, even in this place of death, the forms of state and structure persisted. Secretaries typed. Guards stood post. Goebbels drafted statements. Otto Günsche stood ready for Hitler’s final orders. Eva Braun maintained appearances, dressing carefully as though the war might turn or salvation might arrive. All of them were playing out roles long divorced from reality.

Then came the final purge. Hermann Fegelein, Himmler’s liaison and Eva Braun’s brother-in-law, was captured while attempting to flee Berlin in civilian clothes. He carried cash, jewels, and documents. Hitler, having just learned of Himmler’s betrayal, interpreted Fegelein’s flight as confirmation of a broader conspiracy. Despite Eva’s connection to him, Fegelein was court-martialed and sentenced to death.

Magda Goebbels began speaking openly of killing her six children. She said they could not grow up in a world without Hitler. Others in the bunker heard her with horror but said nothing. Resistance was unthinkable. These were no longer people planning for survival—they were preparing for sacrifice.

April 27 was not marked by a single decisive moment. It was a day of symbols. Final letters. Final revisions. The slow collapse of illusion. Like the last act of Rienzi, the bunker was filled with smoke and betrayal, loyalty and doom. But unlike the opera, there was no soaring redemption. Only silence, poison, and flame.

FULL SERIES:

Yes, Hitler Really Did Commit Suicide, 80 Years Ago

Part 1: April 20, 1945 – Hitler’s Last Birthday

Part 2: April 21, 1945 – The Net Tightens

Part 3: April 22, 1945 – The Breaking Point

Part 4: April 23, 1945 – The Succession Panic

Part 5: April 24, 1945 – The Axis of Betrayal

Part 6: April 25, 1945 – No Way Out

Part 7: April 26, 1945 – The Sky Closes

Part 8: April 27, 1945 – Rienzi

Part 9: April 28, 1945 – Wedding Day

Part 10: April 29, 1945 – The Day Before the End

Leave a Reply