A Hundred Years Ago This Month

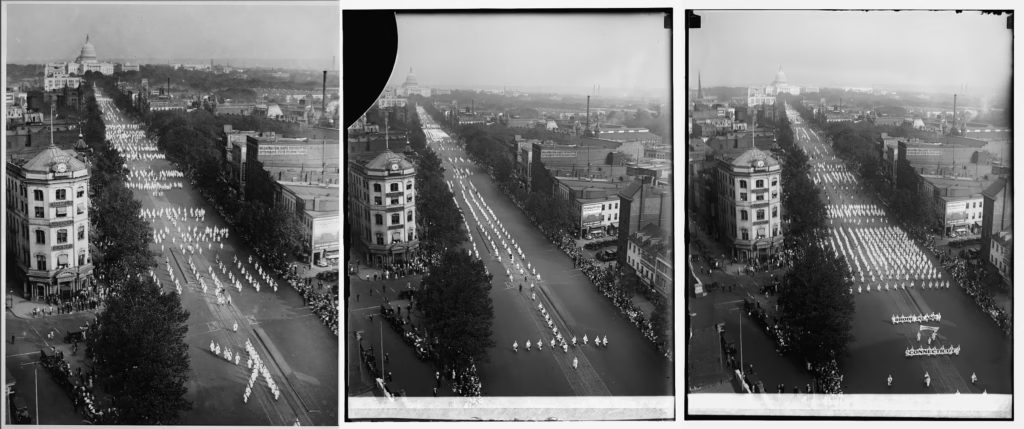

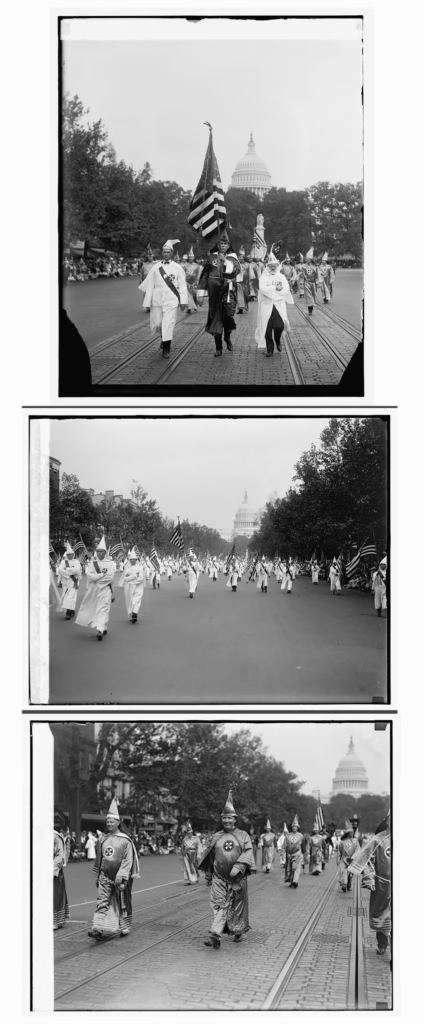

A hundred years may seem like a long time, but in historical terms it isn’t. Just a century ago, in 1925, Washington, D.C. saw its first of two massive Ku Klux Klan rallies (the second was a year later). These weren’t hidden, nighttime gatherings in remote southern towns; these were broad daylight parades down Pennsylvania Avenue, with tens of thousands of robed and hooded Klansmen marching past the seat of American democracy, the U.S. Capitol and the White House. The Lincoln Memorial—dedicated only in 1922, in a ceremony where African Americans were kept segregated in the back—was just down the way, a silent witness to it all.

The New York Times described the scene: “the throngs moved with silent precision, banners aloft, in a show of force meant to impress upon the nation the Klan’s strength and reach.”

And this wasn’t a one-time event: there were two major national Klan marches in Washington, one in August 1925 and another in September 1926, each drawing tens of thousands of marchers in full regalia onto the streets of the nation’s capital.

The Black press reacted with outrage and sadness. NAACP’s The Crisis and papers like The Chicago Defender framed the parade as a national embarrassment—proof that white supremacy could still flaunt its power in the very capital of democracy. Some warned that the march was not just a spectacle but a direct threat to civil rights and personal safety, while others used it to call for renewed political activism and voter registration drives to resist intimidation.

This didn’t happen in isolation. The North may have won the Civil War militarily, but it lost the peace. Reconstruction collapsed under white resistance, and with it came a wave of racial violence and voter suppression. African Americans, newly freed and briefly empowered, were shoved back into poverty and second-class citizenship. And the entire South, insulated from industrial progress and locked into racial hierarchy, was kept backward in many ways.

Then came D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation in 1915, the first true Hollywood blockbuster. It pioneered camera techniques and epic storytelling, dazzling audiences with something they had never seen before. But its content was poisonous. Black people were portrayed as lazy, untrustworthy, and sexually predatory—“the usual stereotypes” of the Jim Crow imagination—and most of those “black” characters were played by white actors in blackface. The “happy ending” Griffith gave audiences? A triumphant Ku Klux Klan charging in to stop Black citizens from voting. Let that sink in: America’s first cinematic epic, the one that put Hollywood on the cultural map, celebrated suppressing Black voters as a heroic act.

The film didn’t emerge in a vacuum; it reflected the Lost Cause narrative that romanticized the Confederacy as having fought for something noble and chivalrous rather than to preserve slavery. That idea had seeped far beyond popular entertainment; it dominated much of academia and public life. President Woodrow Wilson, a former university president and historian, even screened The Birth of a Nation in the White House. The novel it was based on—The Clansman—had been written by Thomas Dixon Jr., one of Wilson’s old college friends. None of this struck most of white society as unusual at the time. It fit comfortably within the way the South’s rebellion and its aftermath were being retold to the nation.

That film supercharged the Klan’s image, helping to transform a fading terrorist organization into a mass-membership fraternity claiming millions nationwide. By the mid-1920s, Klan chapters thrived not only in the South but in Midwestern and Western states, even winning political power in places like Indiana, Colorado, and Oregon. When the Klan paraded through Washington in 1925, estimates put the number of marchers at between 25,000 and 50,000. Ordinary men and women from across the country who believed this was what “true Americanism” looked like.

But their fall came almost as quickly as their rise. One major blow came in 1925 with the D.C. Stephenson scandal. Stephenson, the Grand Dragon of Indiana’s Klan and one of the group’s most powerful leaders, was convicted of the brutal rape and murder of Madge Oberholtzer, a young state employee. The details were shocking: kidnapping, assault, and horrific injuries that led to her death. Stephenson had built his reputation as a moral crusader, claiming the Klan defended women and upheld virtue. His crimes ripped that image to shreds, exposing the hypocrisy at the movement’s core. Combined with widespread public revulsion at the Klan’s extremism, membership quickly plummeted.

The fight to right those old wrongs took decades more, culminating in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, which finally dismantled legal segregation and expanded voting rights. But that progress sparked its own backlash, one that continues to this day.

We don’t live in the openly racist America of 100 years ago, where white supremacists could march in the capital in full regalia without shame. But we do live in an age when many of those same resentments have reemerged, repackaged, and often spread online instead of on parade. The same misguided feelings and ideas are still trying to reshape both our history and our future.

Leave a Reply