People often talk about how they don’t want to vote for “the lesser of two evils.” They want to vote for something they believe in, something better. I used to repeat this sentiment myself, particularly in the 1990s when I refused to vote for any major party candidate for anything. There is a fundamental flaw with this phrase, however, because it assumes that everything is evil; that some version of evil is your only choice. Americans know little of true evil. Few of us have seen it up close and personal or even come anywhere near it. We’re not making choices between evils most of the time; we’re making choices between things we might not care for, might not like, or not fully support. But this is a far cry from evil.

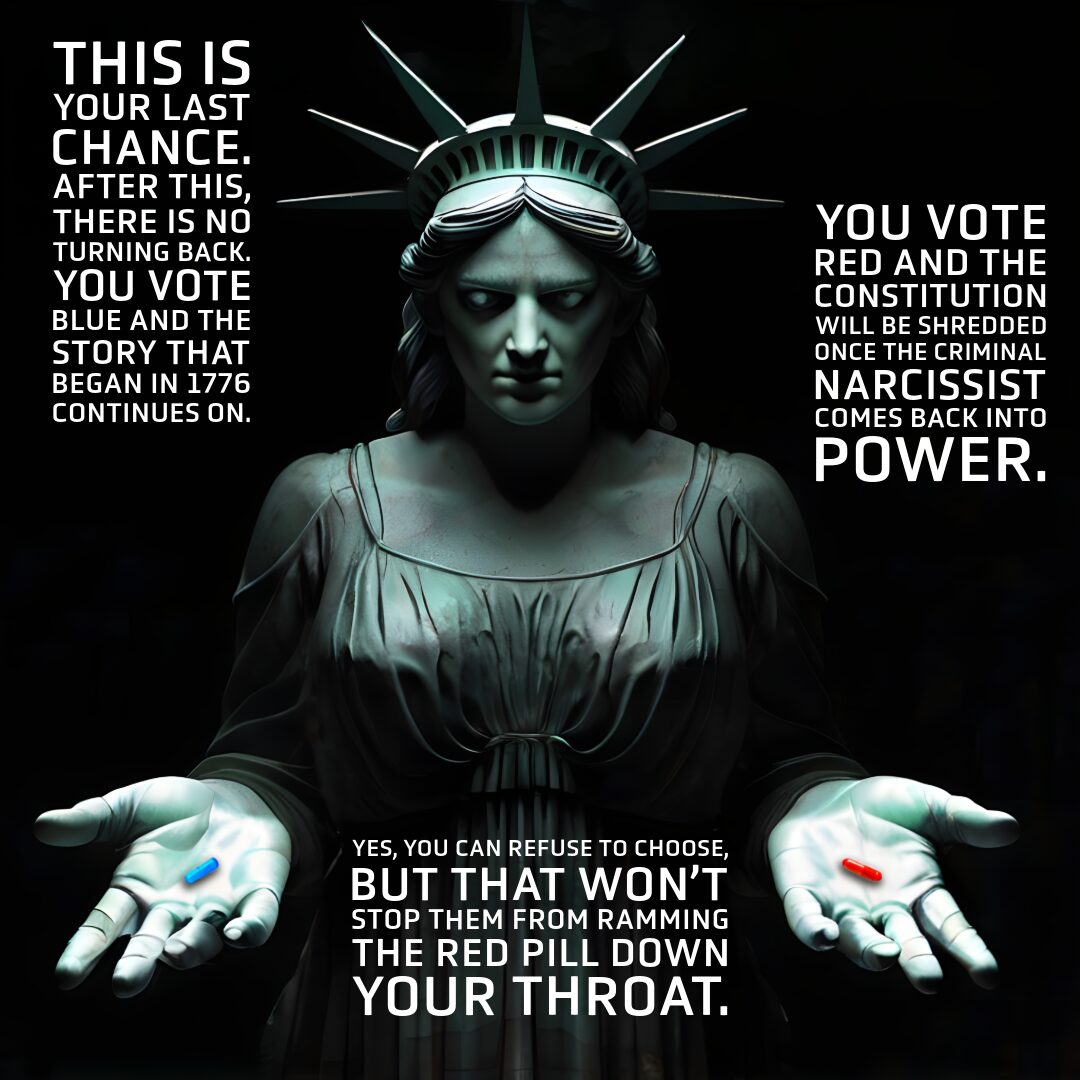

Some will absolve themselves from responsibility by saying, “Don’t blame me, I voted third party,” or, “I didn’t even vote,” as if their refusal to meet the reality of the moment head-on is a virtue. Now that the Supreme Court has spoken, granting Trump king-like immunity in many ways, and most of the justice system is slogging along through the weeds, getting nowhere on Trump’s most substantial criminal charges, this is no time to talk about, “the lesser of two evils.” This is a time for The People to save the things we too often take for granted.

In 1848, the United States was grappling with the aftermath of the Mexican-American War, which had ended the previous year. The war had been deeply divisive, with many Whigs, including Abraham Lincoln, vocally opposing it as an unjust and unconstitutional land grab. The Whig Party itself was fracturing, with the anti-slavery faction clashing with the pro-slavery Southern wing. This division would ultimately lead to the party’s demise and the birth of the Republican Party.

The issue of slavery’s expansion into the newly acquired territories from Mexico was a powder keg waiting to explode. The Democratic Party, led by Lewis Cass, was seen as more likely to allow slavery to spread, while the Whigs, with their diverse views, offered a potential bulwark against it. This was the reality that Representative Lincoln (serving his one and only term in Congress) found himself living in when he decided to travel to Massachusetts and campaign for the Whig presidential candidate, Zachary Taylor.

Lincoln was a staunch member of the anti-slavery faction, though not an immediate abolitionist, while Taylor was a slave owner. Taylor had also come to public prominence as a general in the Mexican-American War, which Lincoln openly and repeatedly opposed. Despite this gulf between them, Lincoln recognized that Taylor was the better choice compared to Cass, and that is what mattered.

No complete transcripts or copies of Lincoln’s addresses in Massachusetts have been found, but there are fragmentary summaries in local newspapers that outline his arguments. These accounts also suggest that many were already seeing Lincoln as a distinguished figure who stood apart from the average politician. This is from the Boston Daily Advertiser, September 14, 1848:

Mr. Lincoln has a very tall and thin figure, with an intellectual face, showing a searching mind, and a cool judgment. He spoke in a clear and cool, and very eloquent manner, for an hour and a half, carrying the audience with him in his able arguments and brilliant illustrations—only interrupted by warm and frequent applause. He began by expressing a real feeling of modesty in addressing an audience “this side of the mountains,” a part of the country where, in the opinion of the people of his section, everybody was supposed to be instructed and wise. But he had devoted his attention to the question of the coming Presidential election, and was not unwilling to exchange with all whom he might meet the ideas to which he had arrived.

…

Mr. Lincoln proceeded to examine the absurdity of an attempt to make a platform or creed for a national party, to all parts of which all must consent and agree, when it was clearly the intention and the true philosophy of our government, that in Congress all opinions and principles should be represented, and that when the wisdom of all had been compared and united, the will of the majority should be carried out. On this ground he conceived (and the audience seemed to go with him) that General Taylor held correct, sound republican principles.

Mr. Lincoln then passed to the subject of slavery in the States, saying that the people of Illinois agreed entirely with the people of Massachusetts on this subject, except perhaps that they did not keep so constantly thinking about it. All agreed that slavery was an evil, but that we were not responsible for it and cannot affect it in States of this Union where we do not live. But, the question of the extension of slavery to new territories of this country, is a part of our responsibility and care, and is under our control. In opposition to this Mr. L. believed that the self named “Free Soil” party, was far behind the Whigs. Both parties opposed the extension. As he understood it the new party had no principle except this opposition. If their platform held any other, it was in such a general way that it was like the pair of pantaloons the Yankee pedler [sic] offered for sale, “large enough for any man, small enough for any boy.”

While Lincoln did not say that voters needed to vote for the “lesser of two evils,” which is a fairly modern phrase, he clearly presented the practical reality that there were two viable choices and one was better than the other in a critical way. Lincoln’s actions in 1848 demonstrated that he understood the imperfections of the democratic-republican system but believed it was still “the last best hope of earth.” Unlike the “Divine Right of Kings and other absurd doctrines,” the American system took humanity’s flaws for granted and asked how best to govern given those imperfections.

Lincoln went on to lose his House seat in the 1848 election, but his national reputation grew. His principled yet pragmatic stance foreshadowed his later presidency and his approach to governance during the Civil War, the approach that saved the Union.

Lincoln’s goal was to hold the line against the expansion of slavery, in the hope that someday it could be done away with or that it would wither away. Today, we are doing more than just holding the line. We are choosing between preserving the republic or abandoning it. The choices we make now will determine the future of our republic. As in Lincoln’s time, we must recognize the stakes and act accordingly, understanding that the preservation of our constitutional system and the rule of law are essential to our continued growth and prosperity.

Leave a Reply